In this article, I’ll talk about a modeling technique called Goal Trees and how I’ve found it useful for leading software engineering teams.

Back in grad school, I developed JSDSI, an open source Java implementation of Carl Ellison’s Simple public key infrastructure and Ron Rivest & Butler Lampson’s Simple distributed security infrastructure. This work taught me about Java development, public key infrastructure, and computer system security. I read a lot about security at that time, including Bruce Schneier’s book Secrets & Lies, which helped me understand the similarities between computer system security and real-world physical security. I particularly liked Schneier’s threat modeling technique, Attack Trees.

Attack Trees are a kind of And-or tree in which each node is a goal, and that node’s children are either alternative ways to achieve that goal (an “or-node”) or are all required to achieve the goal (an “and-node”). In an attack tree, the root node is the goal for a system’s attacker, and the subtrees explore possible ways for the attacker to succeed. Attack trees can be annotated with the likelihood and costs of various subgoals to help defenders anticipate the most likely attacks and make them more costly for the attacker.

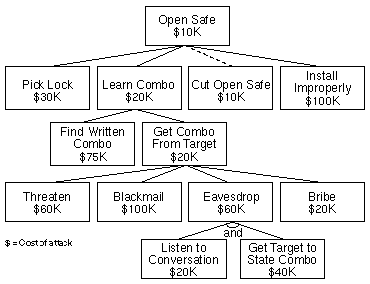

Here’s an example from Schneier’s 1999 article:

In this attack tree, the attacker’s goal is “Open Safe”, and each child “Pick Lock”, “Learn Combo”, etc. is an alternative way to achieve that goal. “Eavesdrop” is the only and-node in the tree, with “Listen to Conversation” and “Get Target to State Combo” as the required subgoals. Schneier has annotated this attack tree with the cost of achieving each goal: the cost of an and-node is the sum of its children’s costs; the cost of an or-node is the cheapest of its children. “Cut Open Safe” is the cheapest way for the attacker to achieve the top-level goal. A defender can use this analysis to make attacks more costly, for example, by expanding “Cut Open Safe” into an and-node that also requires “Gain Access to Safe” and making that more difficult with additional physical security.

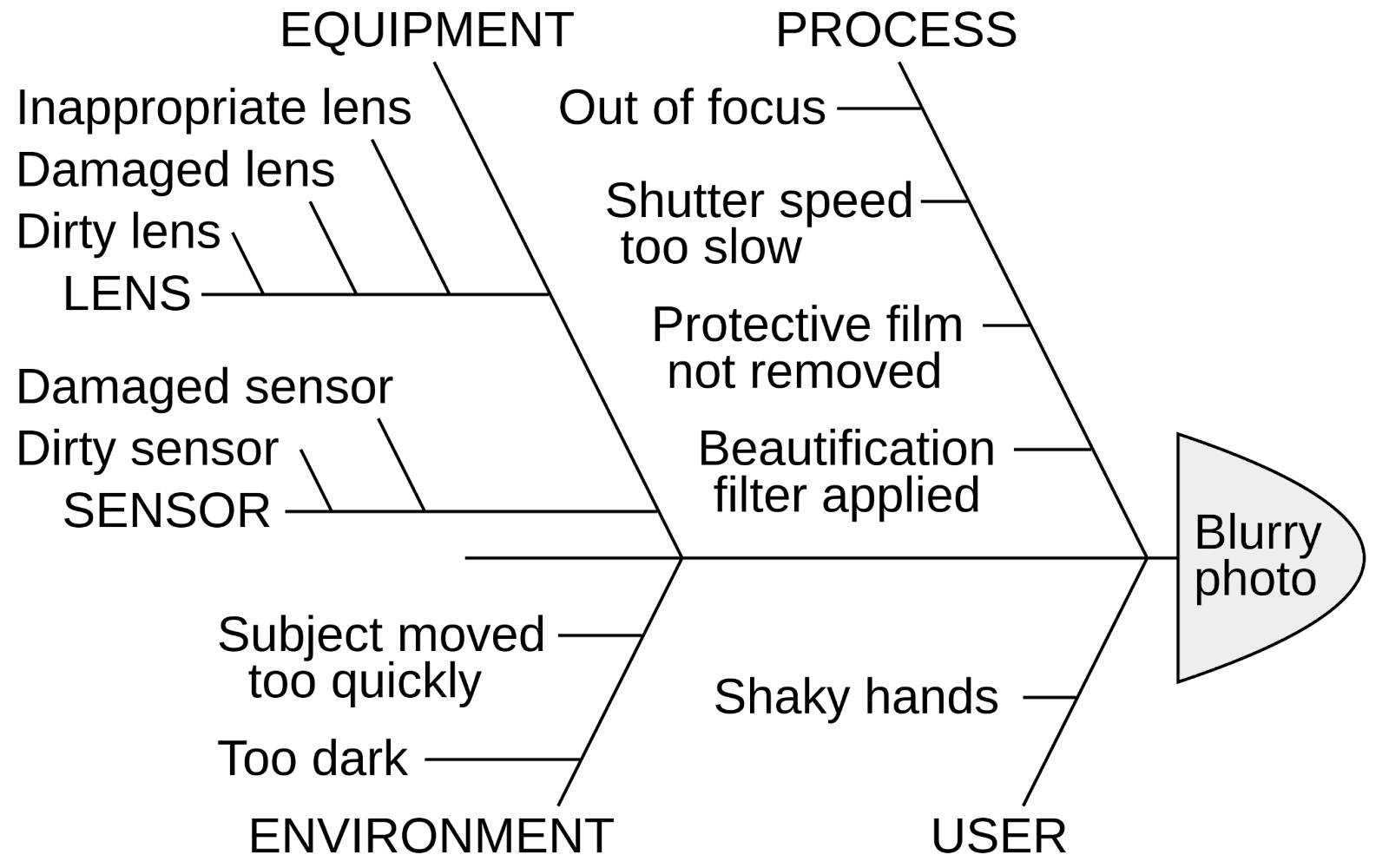

In researching this article, I learned that in 1962, 37 years before Schneier published his article on Attack Trees, Bell Laboratories had developed a similar technique called Fault tree analysis. Ishikawa diagrams (pictured below) were also popularized in the 1960s. These techniques fall under the general category of Root cause analysis, which includes popular quality control techniques like the Five whys.

In software engineering teams, we use related techniques in several areas:

- Recursive goal decomposition: OKRs (Objectives and Key Results) were introduced by Andy Grove at Intel in the 1970s and popularized in his 1983 book, High Output Management. OKRs have been standard practice at Google since 1999. In a large company like Google, it is common for sub-organizations to align their Objectives with one or more of their parent org’s Os or KRs, forming a goal tree, with lower level goals contributing to higher level ones.

- Exploration of alternatives: When designing software to address a product or business requirement, we explore alternative implementations that vary in cost, complexity, and capability. In a system connected by abstractions or interfaces, we can explore alternative implementations of each interface. In these cases, each interface or requirement is an or-node in our goal tree.

- Root cause analysis: Following an outage or system failure, production teams perform a root cause analysis to determine the factors that contributed to the failure. Similar to defending against attacks, we identify ways to make failures less likely by systematically addressing various paths from root causes to the failures.

In my role as an engineering leader, I’ve found these techniques most useful for addressing questions like “should we pursue this idea?” and “why are we doing this project?” These questions come up often for teams building software that doesn’t generate revenue directly, such as those building infrastructure or developer tools and languages. It’s important to have a clear understanding of how these efforts connect to a company’s business goals, such as attracting developers to your platform or streamlining usage of revenue-generating products and services.

(Cue “Is this good for the company?” reference from Office Space.)

Let’s explore this with an example. Suppose a team member comes to you with an idea, like “we should provide a tool that enables automatic migration from older to newer versions of a package”. Such a tool is useful when the new version is not backwards compatible with the old version, that is, client code must change in order to use the new version. Such changes are usually onerous and error prone, so a tool would make this much faster and easier for the user. Sounds great, right?

But in an organization with limited resources, pursuing this project means that less is available for other projects. We need to consider carefully how this project aligns with our organizational goals, what it would truly take to make the idea truly useful, and whether there are better ways to achieve our goals. Here are three steps:

- Climb the goal tree. Use successive “whys” to connect ideas up to organizational goals.

- Complete the solution. Use and-nodes to flesh out complete solutions and estimate their total costs.

- Explore alternatives. Use or-nodes to explore alternative ways to achieve the organizational goals.

Climb the goal tree. Use successive “whys” to connect ideas up to organizational goals.

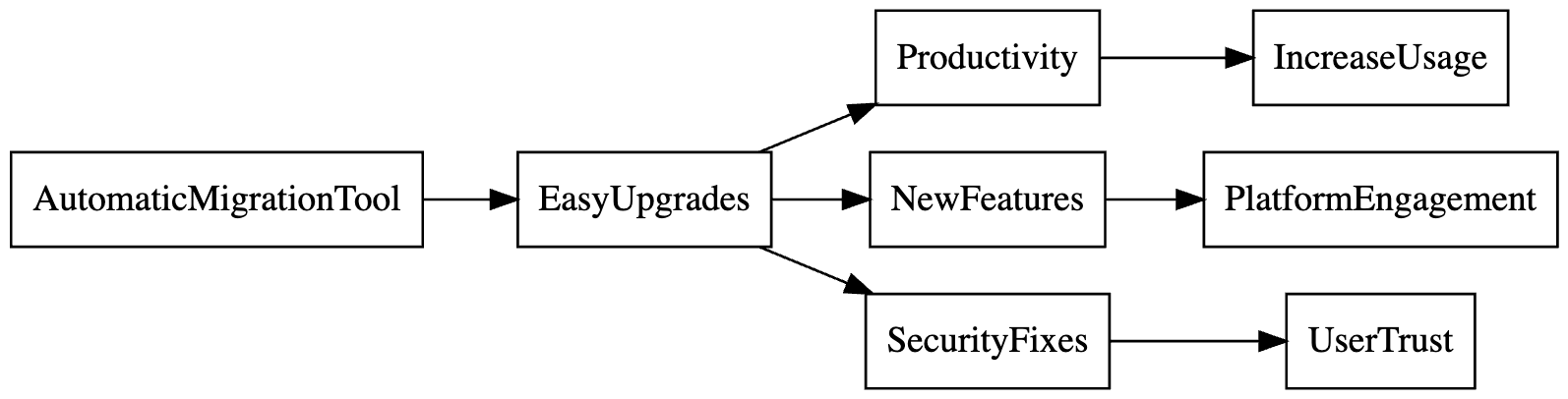

Let’s ask “why” starting from our idea of “provide a tool that enables automatic migration from older to newer versions of a package”:

- Why should we provide an automatic migration tool? To enable users to upgrade to newer versions of packages quickly and easily.

- Why should users upgrade to newer versions of packages? To enable them to be more productive with those packages and gain access to improvements, like new features and security fixes.

- There’s a split here into multiple branches:

- Why should we make users more productive? To increase their use of our platforms and services.

- Why is it important that users gain access to new features? So that they engage with new platform offerings provided through those features.

- Why is it important that users get security fixes? So that users trust the software they build using our packages.

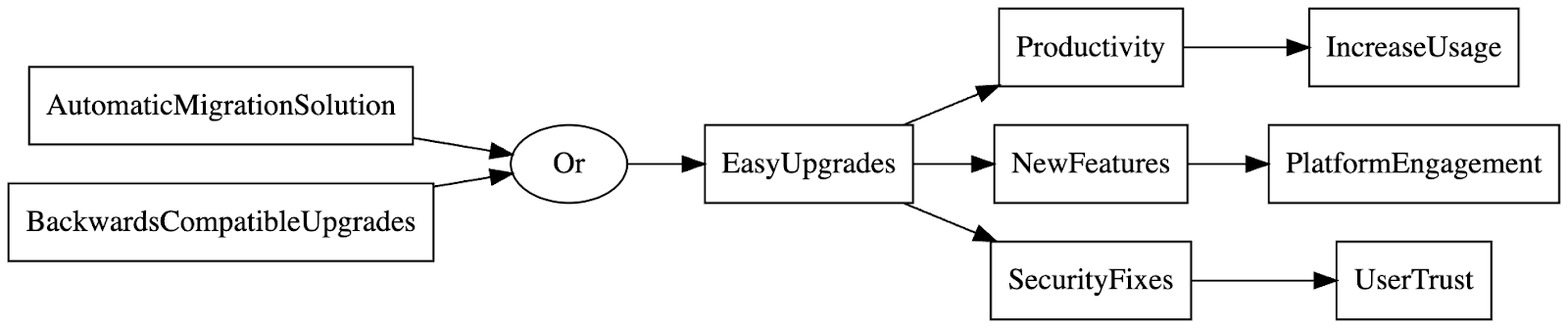

Visualizing these relationships, we connect our AutomaticMigrationTool idea up to the EasyUpgrades goal and to each organizational goal that this serves.

When planning, I’ll use this exercise to connect our project ideas up to the OKRs for my parent organizations as a way of ensuring we’re working on the right things. Even if a project idea doesn’t align with current organizational goals, I can use this analysis to articulate the opportunities the idea creates for the organization.

Sometimes it can be challenging to get team members to think about why and whether we should pursue an idea; instead they are preoccupied with the details of how we’ll implement the idea. In such cases I’ve developed a technique called “Assume success! … then what?” The idea is to remove any doubt that the team is capable of delivering on the idea: I have complete confidence in you, and I will support you if we decide to pursue this! But let’s discuss the impact we hope to achieve by doing this and what it will take to achieve that impact.

Complete the solution. Use and-nodes to flesh out complete solutions and estimate their total costs.

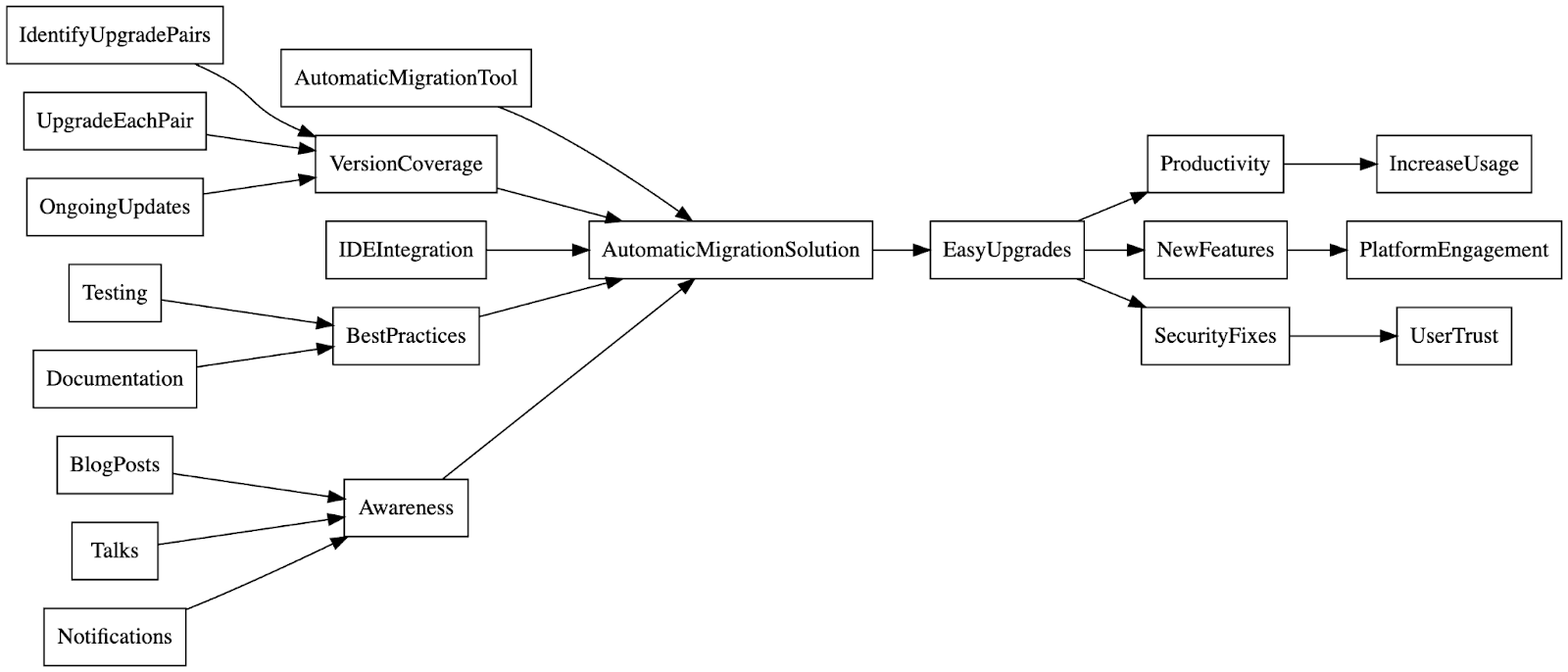

The original idea was “provide a tool that enables automatic migration from older to newer versions of a package”. This is the core technology of an offering, but not a complete solution. In the previous step, we connected this idea to the goal “Enable users to upgrade to newer versions of packages quickly and easily.” If we treat this goal as an and-node, what is needed to actually achieve this goal?

- We need to support migration for each new package version that’s of interest to our business

- We need to identify pairs of old & new package versions

- We need to provide tools to enable migration between each such pair

- We need to repeat this process for each new package version that requires migration

- We should also streamline usage of these tools through IDE integration

- We need to do all the usual best practices: testing, documentation, etc.

- We need to make users aware of these tools through blog posts, talks, notifications

In our picture, we replace the AutomaticMigrationTool node with the and-node AutomaticMigrationSolution, with children for each component of the complete solution.

Surprise! Our goal tree is in fact a goal graph: each goal may connect up to multiple higher-level goals and decompose into multiple subgoals. This is particularly common for projects “further down the stack”, like infrastructure and tools.

We can repeat and-node expansion for each higher-level goal our idea contributes to; for example, providing automatic upgrades for security fixes may require special consideration. This exercise helps us understand the real costs of achieving these goals beyond the core idea.

Explore alternatives. Use or-nodes to explore alternative ways to achieve the organizational goals.

Once we’ve done the and-node expansions, we can consider or-nodes. For each of the goals we’re examining, what are the alternative ways to achieve them? For the goal “Enable users to upgrade to newer versions of packages quickly and easily,” there’s a clear alternative, which is to ensure new package versions are backwards compatible with old ones. Then, updates require no updates to client code. We visualize this as an or-node under EasyUpgrades:

However, this BackwardsCompatibleUpgrades alternative is not free; let’s flesh out the complete solution with an and-node:

- We need to ensure new versions of packages are backwards compatible with old ones by detecting when unreleased new versions are incompatible and blocking their release.

- Detect when a new package version would break the build of client code.

- Detect when a new package version would violate the expectations of client code (typically by breaking tests or benchmarks for client code).

- We need to provide ways to achieve our business goals while maintaining backwards compatibility, for example, by maintaining support for old features while recommending new ones.

These costs add up, and we must weigh them against the alternative of making breaking changes and providing migration support. For example, Go’s compatibility policy guarantees backwards compatibility except when critical fixes, such as for security issues, require a breaking change. In such cases it might makes sense to provide tooling to ease the migration to the new version.

Let’s visualize all this as a complete solution:

Another complexity is that we can only ensure backwards compatibility for packages that we ourselves control. We have no control over whether third-party package authors make breaking changes. We have set a standard for how Go modules (package collections) use semantic version numbers to differentiate compatible and incompatible updates, but we have no way to enforce this. Instead, we can provide tools to help package authors avoid making breaking changes (as we do for ourselves) and to help package consumers identify which packages follow our compatibility guidelines. I’ll explore this further in a future article.

We can apply or-nodes at higher levels of the goal tree: for example, there are many ways to foster user trust beyond making security upgrades easier, such as improving transparency and communication with users. Higher levels of leadership explore these alternatives to decide which major programs to invest in.

Goal Graphs and Cycles. As we saw in the examples above, a subgoal may serve multiple higher-level goals, and each higher-level goal may have several subgoals. This means our goal tree isn’t actually a tree at all, but a graph, with nodes representing goals and edges connecting them. We can annotate the edges in this graph with likelihoods and costs, as we saw with Attack Trees.

It’s tempting to believe that Goal Graphs are acyclic, since completing subgoals should lead to achieving the higher-level goals. But in reality goals are part of a dynamic system, and the state of one goal affects others—even itself! Making progress towards one goal may accelerate or impede progress towards other goals.

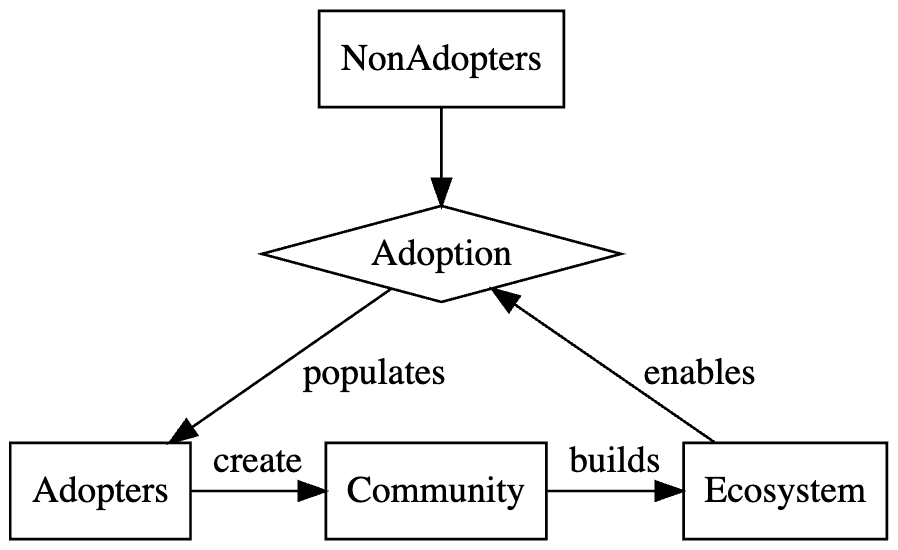

The simplest example of this is product adoption. It’s common for product adoption to be a goal for an organization, and many dream of the “hockey stick” of exponential growth. The key to such rapid growth is network effects: a product becomes more attractive as more people use it. This is clearly true for social networks, but it’s also true for developer tools and languages. More adoption leads to a richer community and ecosystem of documentation, trainings, packages, tools, meetups, conferences, forums, and more … all of which leads to more adoption. This is a positive feedback loop.

We can visualize Adoption as a flow between two stocks, NonAdopters and Adopters, with the Ecosystem enabling that flow:

Adoption continues growing until the product saturates its market or some other factor limits it. Goals of accelerating product adoption typically involve removing a limiting factor or a negative feedback loop. At this point we’ve moved from goal analysis to system dynamics. If you find this interesting, I recommend Thinking in Systems by Donella Meadows.

In this article, we’ve explored ways of thinking about project ideas, organizational goals, and the exploration of alternatives. In future articles I’ll discuss ideas around improving stability and security in open source package ecosystems and how we define SLOs (service level objectives) for developer tools and languages.

You must be logged in to post a comment.